I resolved to begin reading Americanah because of Beyonce. Not the most original reason, I know. It wouldn’t stun me if other steadfast readers of fiction were set off on Chimamanda Ngoiz Adichie’s international adventure by Bey’s MTV awards show spectacular. But, for those readers who are confused about the connection between a novel by a Nigerian born American immigrant and one of America’s biggest celebrity icons, let me explain.

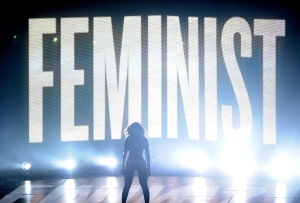

Those that have better things to do than watch MTV’s awards show…or don’t read Salon, Slate, Jezebel, The Huffington Post, Upworthy, or Buzzfeed…wouldn’t know that Bey’s performance involved an incredibly striking moment in which she was backlit by the word FEMINIST on a hefty screen: score one for celebrities being outspoken about feminism.

This strong statement to American Pop Culture was followed by an audio quote from a speech Chimamanda Adichie, the author of Americanah, gave about feminism at TEDxEuston:

My partner, who like me has been weary of Beyonce as a spokes-figure for feminism in the past, was pleased with Yonce’s impactful move. I felt differently. Though I could acknowledge that a well respected celebrity raising the jumbotron banner for feminism would push its message to more people and work towards wider social acceptance for a belief system that arguably everyone should have accepted by now anyway, I could not get past the fact that this message came just minutes after a pyramid of glitter covered butts humped the stage.

Not butts on bodies of all shapes and size, but butts on a very particular female body that can most often be found on the covers of men’s magazines. It’s difficult, I argued with my partner, to take Yonce seriously as a celebrity spokes-woman for feminism when she is also so distinctly contributing (directly or indirectly) to the business of the objectification of women.

“Who are you to say how she can and cannot express her sexuality. Who are you to say what woman can and cannot wear,” my partner was quick to point out. A fight ensued. I will spare readers the dirty details, but my partner is currently sitting next to me and laughing as I type. For some reason during that fight, I felt that Chimamanda Adichie could have answers for some of the questions that were bouncing around in my head.

Alright, at this point I suppose it’s important to admit the truth. You’ve all been wondering anyway and there’s no point in keeping you distracted by not just telling you. I’m male…well, no I’m a white male…well…fine, I’m a white middle-class male; I am also a feminist. Well, a white middle-class male feminist: I’ve found that those qualifiers are important. Though I may be able to intellectually support the equality of the sexes, I have not personally been in the position of the unequal. I have only ever reaped the benefits of the hand I have been dealt, and my royal flush means that I don’t know what it’s like to play with a bad hand. My role in the feminist movement should be one of listening, learning to understand, empathizing, and leading by example to others who may not be allies. Out of all those tasks, I am coming to discover that empathizing is one of the most crucial.

I would love to say that we comprehend empathy in America, but the older I get the more I find that a portion of our population hasn’t quite figured empathy out. If you want to know what I am talking about, just take a look at this video of Cardinals fans engaging in a shouting match with Ferguson, MO protestors. It appears as though the Cards fans are more interested in belittling the actions and tearing down the statements of those who are shouting about injustices they have faced. Rather than listening and attempting to empathize, the fans seem determined to tear down the legitimacy of the protesters. However, if the Cardinals shouters did try to exercise their empathy muscle, it would be the Right Supramarginal Gyrus that would be pumping the unassuming iron, and, let me tell you, if you are a WMM (white, middle-class, male) Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah is quite the workout.

WARNING INCOMING BOOK DESCRIPTION ALL THOSE THAT HAVE ALREADY READ THE BOOK SHOULD EVACUATE THE AREA:

The novel Americanah follows Ifemelu, a female african who travels from her home in Nigeria to America and eventually returns back to her home in Nigeria. Two main plots track her adventures: her observations on race in America and her relationships with a series of men. While in America she starts a blog called “Raceteenth or Various Observations About American Blacks (Those Formerly Known as Negroes) by a Non-American Black” (4).

A majority of the book spends its words focusing on misunderstood empathy from two different fronts, gender relations and race relations. Ifemelu faces gender oppression in Nigeria more than she does in America (though she faces it in American as well), but faces race oppression exclusively in America. This racism based on the color of her skin is wholly new to Ifemelu when she arrives in America, and her observations about this fact are the central concept in the book. They are summed up in one of her blog posts, “Dear Non-American Black, when you make the choice to come to America, you become black” (273). These blog posts are the points in the book were I felt that Chimamanda, the author, was speaking directly to me, the reader. Not Chimamanda through Ifemelu, but Chimamanda the person.

The prose in her blog posts is personal and raw. In fact, they are so personal that, considering Chimamanda’s life story, it’s impossible not to feel their message in that enflamed and immediate non-fictional way. As an immigrant, Chimamanda has the perspective to point things out that readers, the ones who live the American context everyday, may not be able to see wholly. Just as it’s difficult to see the gigantic whitehead on your forehead without someone holding up a mirror for you, it’s often difficult for us to see the smelly puss filled whiteheads in our society until they pop.

But, during these blog sections of the novel, I sometimes found myself wanting to shout, “yes I agree with what you’re saying, this race situation sucks a lot; I don’t need to be lectured at about it; I’m on your side already.” At one point I actually wrote those words in black ink across a whole page. But as I stared at my own writing overlapping Adichie’s prose, it quickly dawned on me that I was negating what I often argue is the principle reason why people should still read novels: to listen and through listening step into the consciousness of somebody else, for 300 or so pages, to better understand a unfamiliar life experience. Scientists have argued that the Right Supramarginal Gyrus allows us to overcome emotional egocentricity. In this way, empathy isn’t just imagining yourself in another’s shoes, but actually allowing yourself to bleed into the background, to belittle your own thoughts and feelings in order to allow another’s to take prominence (even control) without judgment. I believe that literature is an art form where this emotional practice can be taught and easily experienced; you know that feeling: when you are actually becoming the character in a novel, when their story sucks you in so deep you forget your even reading tiny little ink marks on a page. But I didn’t get that feeling during Americanah because I was more interested in jumping to my defense against Chimamanda’s biting social observations than actually listening without judgment; I was failing to fully empathize.

I came to Americanah with absolutely no point of reference: Ifemelu grew up as a woman in a struggling family living in Nigeria; I grew up as a male in a middle-class suburb of St. Louis Missouri. In fact, and it pains me to say this, if I fall, kicking and screaming, into any category of character from the novel it is most likely the liberal, educated, self-appointed anti-racists that Ifemelu encounters in America. One of these characters is the “dreadlocked white man”(4) she meets in passing on the bus. As they get into a conversation about her blog, this character states that “Race is totally overhyped these days, black people need to get over themselves, it’s all about class now, the haves and the have-nots”(4-5).

Now, his comments aren’t racist per-say; Dreadlocks isn’t making any claim about all Blacks based on their race, but he is discounting their life experiences. Instead of listening and attempting to accept the truth of another’s life, this character makes it clear that he is more interested in asserting his own belief that racism no longer exists “these days”. His observation is weaved with a sentiment of exhaustion. You can feel his desperation to be done with the seeming unsolvable race issue, to place the blame elsewhere. I am sure that for those non-blacks who legitimately aren’t racist it would be easier if everyone else was automatically on that same page. That’s not to say that class isn’t an issue as well, dreadlocks isn’t wrong in that assertion, but he is unfounded in the other. In this same way, maybe it’s more important for me to listen to Beyonce’s message than to complain about her dancers.

It seems to me that some people who have not experienced racial oppression try to devalue the claims of those who have by shifting the issue from race to class, like the person in the above Cardinals video who shouted, “That’s right! If they’d be working, we wouldn’t have this problem!” The fervor with which some of those who are unaffected by racial injustice jump to the class issue when talking about Ferguson displays their contempt for people playing “the race card”. But, as Obinze, Ifemelu’s lover, observes, “A white boy and a black girl who grow up in the same working-class town in this country (England) can get together and race will be secondary, but in America, even if the white boy and black girl grow up in the same neighborhood, race would be primary” (340). It’s almost as if those who don’t live with these problems everyday are often afraid to talk about race, and I suppose it’s understandable. It’s difficult to talk about something that you feel you have little control over. But the point isn’t for white people (me) to talk, it’s for them (me) to listen.

Throughout the book is a sense that liberal non-black Americans don’t want to be intimidated. In another blog post, Ifemelu writes, “If you are a woman, please do not speak your mind as you are used to doing in your country. Because in America, strong-minded black women are SCARY. And if you are man, be hyper-mellow, never get too excited, or somebody will worry that you’re about to pull a gun…If you’re telling a non-black person about something racist that happened to you, maker sure you are no bitter. Don’t complain. Be forgiving…Most of all, do not be angry. Black people are not supposed to be angry about racism. Otherwise you get no sympathy” (274-275).

And isn’t there a painful truth to her words? People don’t want to feel like they have to hand over control of their emotions to another person, but this is exactly what empathy requires, a relinquishment of the power to feel how you want about a situation. In our Upworthy/Buzzfeed world, some people only want others to share their emotions in a positive way (“if you don’t have anything nice to say don’t say anything at all”). This sentiment is all well and good until you think of a person who has lived in a system of injustice their whole life and they might actually want to say things that aren’t necessarily “nice”.

I have seen even the most strident defenders of equality get uncomfortable or angry when in conversation with blacks who want to express their anger over mistreatment. I have seen liberals want to jump in and defend non-blacks “who aren’t like that” and claim that the people their black friend is talking about are outliers. In my experience, blacks often aren’t telling these stories to make sweeping claims about all non-blacks being racists (though non-blacks may subconsciously feel that way). I have found that they are often sharing these stories of racism because blacks just want non-blacks to listen, because they want to share their experience with someone else and have that person absorb their emotions.

It has been my experience that some people want to be supporters of anti-racism but only on their own terms. If being a supporter involves being uncomfortable as a person who has faced injustice expresses their anger, even expresses it by shouting in a group or protesting in the streets, than non-black doesn’t feel comfortable supporting that person or want to start imposing caveats on how that person can express themselves. This thought process is obviously also applicable to my arguments against Beyonce. My comments were belittling or delegitimizing her position as a feminist, but it’s not my place to claim that she’s not a feminist. It’s more important to listen (to all feminists not just Beyonce) instead of trying too impose caveats on how she wants to express herself on stage.

Being black means something different in America, and white people (myself) need to understand that. We can’t just talk about how we (white people) feel and why our feelings on racism change the whole of society. The most significant thing we can do is listen, and hear what those who are oppressed are saying without belittling it or shifting it into something else. Maybe if we listen in Ferguson instead of shouting over protestors, we can better understand how to help, and maybe the same goes for Feminism?

In Nigeria, Ifemelu is told that marriage is what women should aspire to while in America she is expected to aspire to a career. In Nigeria, she is expected to get a man while in America she is expected to get a job. Her blog about race is important in America, and that’s why she is accepted into the affluent academic club at Princeton. In Nigeria, this blog would mean little to nothing, but I do wonder if she would have been as accepted by the affluent academic club in America if she would have written a blog about feminism the way she writes a blog about race?

“‘You know why Ifemelu can write that blog, by the way?’ Shan said. ‘Because she’s African. She’s writing from that outside. She doesn’t really feel all the stuff she’s writing about. It’s all quaint and curious to her. SO she can write it and get all these accolades and get invited to give talks. If she were African American, she’d just be labeled angry and shunned'” (418) .

We don’t want to face the pain and negativity that people who have faced injustice actually experience, especially when we feel somehow indirectly culpable, but when it comes with a context of positivity we seem to be able swallow it. We easily guzzle down Upworthy videos and Buzzfeed articles, but find it hard to stomach someone shouting at us as they march in the street. But it shouldn’t be about what’s easy to swallow. It should be about accepting the pill that people who have faced injustice are presenting to us. It’s about listening to shouting Ferguson protestors instead of telling them how to shout; it’s about focusing on how Beyonce’s message changes things instead of telling her how I think she should be presenting it; it’s about unpacking your backpack no matter how heavy or filled it may be, but that doesn’t mean you have to unpack it alone.

Thanks Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie for helping me further unpack my overstuffed backpack.

Adichie, Chimamanda (2013). Americanah. New York: Anchor Books.

Lately owning one’s sexuality has become synonymous with selling it..mostly when a pop-star is involved. I agree with Annie Lennox, who said Beyonce’s was “feminist lite”.

LikeLike